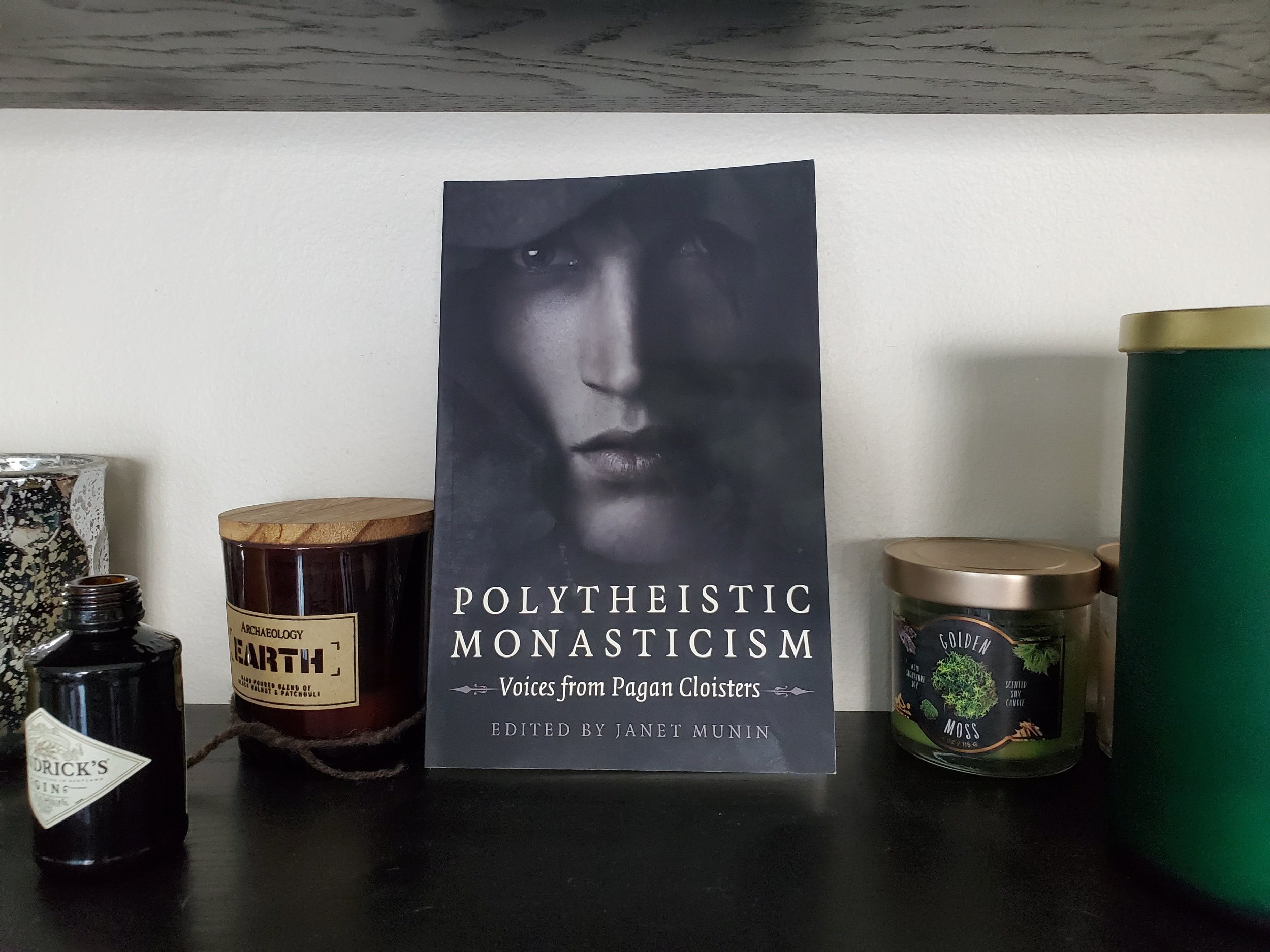

Outside the Charmed Circle: Exploring Gender and Sexuality in Magical Practice

by Misha Magdalene, published in 2020 by Llewellyn

ISBN: 978-0-7387-6132-9

This book was the community pick for the Fellowship Beyond the Star book club for October, suggested by Ron Padrón (of White Rose Witching), and I'm super glad he suggested it (and that it got the second most votes and was therefore next) because I really enjoyed it! I shared one quote that really resonated with me on Facebook when I was partway through the book, and I didn't quite manage to finish the whole thing by the book club date, but I have now and I thought I'd review it for ya'll!

The book is a little under 300 pages, including the foreword by Michelle Belanger (but not including the appendices and the bibliography), written in a sort of lightly academic style that is still pretty accessible. Magdalene makes sure to define new terms for every chapter, and while some of it will be very familiar to those who've done some university-level gender studies, that kind of background isn't at all required to follow her arguments. Her writing is clear and concise, while still leaving room for it to be heartfelt and hilarious at turns.

The first two chapters set us up: introducing the author, the book, and the general terms that will provide the framework for everything else. Magdalene also explains what the "charmed circle" is, a term she borrowed from Gayle Rubin's 1984 essay "Thinking Sex": cultures attribute positive and negative values to sexual attributes, and those that are positively valued are said to be the "charmed circle" of sexuality in that culture, with their opposites, (ie, anything "queer" in our modern western society) falling outside that circle. The third chapter discusses embodiment, and both how magic is embodied (the body being our first magical tool) as well as how gender and sexuality are embodied, and how trauma and disability can disrupt and complicate things (plus some very good suggestions for grounding when they do). Chapter 4 rounds out the first section, with some more gender theory, and a section titled "Opening a Discourse About Gender Essentialism and Other Cans of Worms" that is just pure gold - and, alas, too long to reproduce here in total, but here's a snippet: "Let's talk about 'masculine' and 'feminine' energies, or perhaps we can call them 'active' and 'passive' energies, or positive and negative polarities. While we're at it, we can talk about the equation of masculinity with active, positive and projective qualities, and the consequent equation of femininity with passive, negative, and receptive qualities... but hey, that's not exist, right?" (p.105) Chapter 5, titled "Queerness and the Charmed Circle", returns to the definitions of both queerness and the charmed circle itself, concluding "to be queer is to be intrinsically Other, standing outside the charmed circle of societal approval for the sake of living an authentic life." (p.144)

Chapter 6 gets us into the meat of this and the practical applications, discussing sex magic, in the context of queer sex and embodied magic, and — importantly — consent. This chapter includes a ritual that's a bit longer than the exercises sprinkled throughout the other chapters, though honestly I felt like this chapter has the potential to be another entire book, should Magdalene wish to elaborate further! Continuing on, Chapter 7 is titled "Form Follows Function: Toward A Consent-Based Magical Praxis", and it's in this chapter that I found the quotation I just had to share on Facebook: "If those of us who work with gods, spirits, powers, and our fellow practitioners aren't basing our communities and our praxis in consent, we have no claim to any sort of spiritual advancement or wisdom. We're merely overgrown toddlers who haven't learned that other people, other beings - human or other, corporeal or not, living or dead or something else - don't exist for our convenience, to sate our desires. They have their own agency, just as we do, and understanding that agency should be the core of any interaction, magical or mundane." (pp.181-82) If you want my bare-bones honest opinion, this book is worth buying for that chapter alone. Chapter 8 discusses consent as it applies to our work and relationships with spirits and deities, and I think anyone who is thinking of entering into any kind of contract or devotional relationship with a deity should read it. I don't think enough of us stop to consider our own consent in these relationships, but it matters. Deeply. This chapter covers not only how and when to say no, but also what kind of responses you might get back, and what to do if things go sideways. It is another chapter that could easily be expanded into another entire book — one I would gladly buy for the Fellowship library so I could hand it off to new pagans! Chapter 9 gives several examples of ways to adjust your practice to be more consent-based, and the pros and cons of each, and includes a quick reminder of what cultural appropriation is and how to avoid it. Chapter 10, titled "Greater Than One: Thoughts on Politics, Power, and Community", explains why gender, sexuality, magic, witchcraft, and paganism are all political, and why we can't abstain from political discussions as we build and maintain our communities. It also tackles questions of diversity, inclusivity, the paradox of tolerance, and what it means to lead. The final chapter is short, and is both conclusion and a consideration of what else, what next. Because the work is never done.

I really enjoyed this book and I'm very glad it exists — so much of what I found within its pages was validating and inspiring. If I had to list drawbacks, I can think of only three, and all three make sense in the context of the author herself and that the material, by necessity, had to remain streamlined. First, the magic this book focuses on is predominantly ceremonial magic, which appears to be what Magdalene herself practices, but it is not the backbone of my own practice, so there were points at which I either had little interest in a suggestion or I agreed but while coming from a very different angle. Secondly, the lists of queer deities were very brief and not at all exhaustive (in fact, on of my favorite queer deities, Heimdall, was absent). Very few pantheons were included, but I imagine this was both an attempt to draw on her own experiences (instead of being encyclopedic) and also to give enough space to talk about why the deities included should be considered queer, instead of just giving a list with no justification or explanation. (Llewellyn, if you're reading this, I would LOVE an edited encyclopedia of queer deities, though. Just sayin'.) Thirdly, and this is the smallest of all, in the section on deity relationships and consent, Magdalene rightfully points out that pagans as a whole seem to accept more toxic behaviours from our deities than we would from our romantic partners, and while that is very true in my experience (and ought not to be), I think a little discussion of complicated familial relationships might round out that analogy, because there certainly are deities that I would walk away from if I could, but I can't completely avoid them because of a larger web of relationship — much more like a problematic uncle than a toxic boyfriend. Other than those three little nitpicks, I wholeheartedly recommend this book to any "p-word" community member (that is: Pagans, Polytheists, and magical/occult Practitioners) who is queer, who is trying to be a better queer ally, or who holds any kind of leadership role in their own community.

If you're interested in joining the Fellowship Beyond the Star for our next book club meeting, we'll be meeting on Zoom on January 14th, 2024, 12-2pm Eastern Time, and discussing John Beckett's Paganism in Depth. More details can be found here.